Design Considerations and Best Practices to Modernize Traditional Apps (MTA)

Design Considerations and Best Practices to Modernize Traditional Apps (MTA)¶

Introduction¶

The Docker Containers as a Service (CaaS) platform delivers a secure, managed application environment for developers to build, ship, and run enterprise applications and custom business processes. Containerize legacy apps with Docker Enterprise Edition (EE) to reduce costs, enable portability across infrastructure, and increase security.

What You Will Learn¶

In an enterprise, there can be hundreds or even thousands of traditional or legacy applications developed by in-house and outsourced teams. Application technology stacks can vary from a simple Excel macro, to multi-tier J2EE, all the way to clusters of elastic microservices deployed on a hybrid cloud. Applications are also deployed to several heterogeneous environments (development, test, UAT, staging, production, etc.), each of which can have very different requirements. Packaging an application in a container with its configuration and dependencies guarantees that the application will always work as designed in any environment.

In this document you will learn best practices for modernizing traditional applications with Docker EE. It starts with high-level decisions such as what applications to Dockerize and methodology, then moves on to more detailed decisions such as what components to put in images, what configuration to put in containers, where to put different types of configuration, and finally how to store assets for building images and configuration in version control.

What Applications to Modernize?¶

Deciding which applications to containerize depends on the difficulty of the Dockerizing versus the potential gains in speed, portability, compute density, etc. The following sections describe, in order of increasing difficulty, different categories of components and approaches for containerizing them.

Stateless¶

In general, components which are stateless are the easiest to Dockerize because there is no need to take into account persistent data such as with databases or a shared filesystem. This is also a general best practice for microservices and allows them to scale easier as each new instance can receive requests without any synchronization of state.

Some examples of these are:

- Web servers with static resources — Apache, Nginx, IIS

- Application servers with stateless applications — Tomcat, nodeJS, JBoss, Symphony, .NET

- Microservices — Spring Boot, Play

- Tools — Maven, Gradle, scripts, tests

Stateful¶

Components which are stateful are not necessarily harder to Dockerize. However, because the state of the component must be stored or synchronized with other instances, there are operational considerations.

Some examples of these are:

Application servers with stateful applications — There is often a need to store user sessions in an application. Two approaches to handling this case are to use a load balancer with session affinity to ensure the user always goes to the same container instance or to use an external session persistence mechanism which all container instances share. There are also some components that provide native clustering such as portals or persistence layer caches. It is usually best to let the native software manage synchronization and states between instances. Having the instances on the same overlay network allows them to communicate with each other in a fast, secure way.

Databases — Databases usually need to persist data on a filesystem. The best practice is to only containerize the database engine while keeping its data on the container host itself. This can be done using a host volume, for example:

$ docker run -d \ -v /var/myapp/data:/var/lib/postgresql/data \ postgres

Applications with shared filesystems - Content Management Systems (CMS) use filesystems to store documents such as PDFs, pictures, Word files, etc. This can also be done using a host volume which is often mounted to a shared filesystem so several instances of the CMS can access the files simultaneously.

Complex Product Installation¶

Components that have a complex production installation are usually the hardest to Dockerize because they cannot be captured in a Dockerfile.

Some examples of these are:

- Non-scriptable installation — These can include GUI-only installation/configuration or products that require multi-factor authentication.

- Non-idempotent installation process — Some installation processes can be asynchronous where the installation script has terminated but then starts background processes. The completion of the entire installation process includes waiting for a batch process to run or a cluster to synchronize without returning a signal or clear log message.

- Installation with external dependencies — Some products require an external system to reply for downloading or activation. Sometimes for security reasons this can only be done on a specific network or for a specific amount of time making it difficult to script the installation process.

- Installation that requires fixed IP address — Some products require a fixed IP address for a callback at install time but can then be configured once installed to use a hostname or DNS name. Since container IP address are dynamically generated, the IP address could be difficult to determine at build time.

In this case instead of building an image from a Dockerfile the image should be build by first running a base container, installing the product, and then saving the changes out to an image. An example of this is:

$ docker commit -a "John Smith" -m "Installed CMS" mycontainer cms:2

Note

Tools or Test Container. When debugging services that have

dependencies on each other, it is often helpful to create a

container with tools to test connectivity or the health of a

component. Common cases are network tools like telnet, netcat,

curl, wget, SQL clients, or logging agents. This avoids adding

unnecessary debugging tools to the containers that run the production

loads. One popular image for this is the netshoot troubleshooting

container.

Methodology¶

Two different use cases for modernizing traditional applications are:

- End of Life — Containerizing an application without further development

- Continued Development — Containerizing an application that has ongoing development

Depending on the use case, the methodology for containerizing the application can change. The following sections discuss each of them.

End of Life¶

An application that is at its end of life has no further development or upgrades. There is no development team, and it is only maintained by operations. There is no requirement to deploy the application in multiple environments (development, test, uat, staging, production) because there are no new versions to test. To containerize this type of application, the best solution would be to copy the contents of the existing server into an image. The Docker community provides open source tools such as Image2Docker to do this, which will create a Dockerfile based upon analysis of existing Windows or Linux machines:

Once a Dockerfile is generated with these tools, it can then be further modified and operationalized depending on the complexity of application. An image can then be built from the Dockerfile and run by an operations team in Docker EE.

Continued Development¶

If the application will continue to be actively developed, then there are other considerations to take into account. When containerizing an application it might be tempting to refactor, re-architect, or upgrade it at the same time. We recommend starting with a “lift and shift” approach where the application is first containerized with the minimal amount of changes possible. The application can be regression tested before further modifications are made. Some rules of thumb are:

- Keep the existing application architecture

- Keep the same versions of OS, components, and application

- Keep the deployment simple (static and not elastic)

Once the application is containerized, it will then be much easier and faster to implement and track changes such as:

- Upgrade to a newer version of application server

- Refactor to microservices

- Dynamically scale or elastic deployment

In a “lift and shift” scenario the choice of base libraries or components such as an application server or language version as well as the underlying OS are already determined by the legacy application. The next step is determining the best way to integrate this “stack” into a Docker image. There are several approaches to this depending on the commonality of the components, the customization of components in the application, and adherence to any enterprise support policies. There are different ways to obtain a stack of components in an image:

- Open source image — A community image from Docker Hub

- Docker Certified — A certified image from Docker Hub, built with best practices, tested and validated against the Docker EE platform and APIs, pass security requirements, and are collaboratively supported (eg, Splunk Enterprise)

- Verified Publisher — A verified image from Docker Hub, published and maintained by a commercial entity (eg, Sysdig Inspect)

- Official image — Official Images are a curated set of Docker open source and “drop-in” solution repositories hosted on Docker Hub (eg, nginx, alpine, redis)

- Enterprise image — An internal image built, maintained, and distributed by an enterprise-wide devops team

- Custom image — A custom image built for the application by the development team

While the open source and certified images can be pulled and used “as is” the enterprise and custom images must be built from Dockerfiles. One way of creating an initial Dockerfile is to use the Image2Docker tools mentioned before. Another option is to copy the referenced Dockerfile of an image found in Docker Hub or Store.

The following table summarizes the advantages and disadvantages of each choice:

| Open-source | Certified | Enterprise | Custom | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Advantages |

|

|

|

|

| Disadvantages |

|

|

|

|

A common enterprise scenario is to use a combination of private and custom images. Typically, an enterprise will develop a hierarchy of base images depending on how diverse their technology stacks are. The next section describes this concept.

Image Hierarchy¶

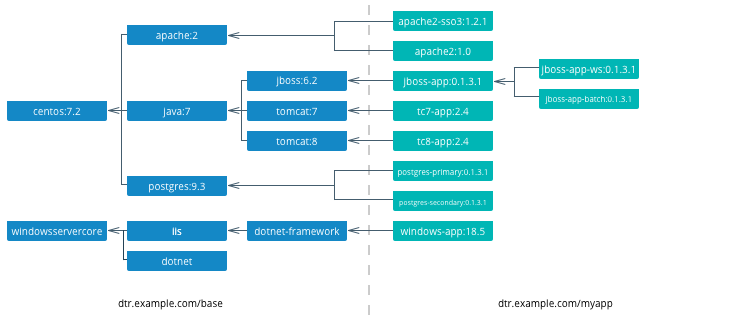

Docker images natively provide inheritance. One of the benefits of deriving from base images is that any changes to a base or upstream image are inherited by the child image simply by rebuilding that image without any change to the child Dockerfile. By using inheritance, an enterprise can very simply enforce policies with no changes to the Dockerfiles for their many applications. Typically, an enterprise will develop a hierarchy of base images depending on how diverse their technology stacks are. The following is an example of an image hierarchy.

On the left are the enterprise-wide base images typically provided by the global operations team, and on the right are the application images. Even on the application side, depending on how large an application or program is, there can be a hierarchy as well.

Note

Create a project base image. In a project team with a complicated application stack there are often common libraries, tools, configurations, or credentials that are specific to the project but not useful to the entire enterprise. Put these items in a “project base image” from which all project images derive.

What to Include in an Image¶

Another question that arises when modernizing is what components of an application stack to put in an image. You can include an entire application stack such as the the official GitLab image, or you can do the opposite, which would be to break up an existing monolithic application into microservices, each residing in its own image.

Image Granularity¶

In general, it is best to have one component per image. For example, a reverse proxy, an application server, or a database engine would each have its own image. What about an example where several web applications (e.g. war) are deployed on the same application server? Should they be separated and each have its own image or should they be in the same image? The criteria for this decision are similar to non-containerized architectural decisions:

- Release Lifecycle — Are the application release schedules tightly coupled or are they independent?

- Runtime Lifecycle — If one application stops functioning should all application be stopped?

- Scalability — Do the applications need to be scaled separately or can they be scaled together?

- Security — Does one application need a higher level of security such as TLS?

- High Availability — Is one application mission critical needing redundancy and the others can tolerate a single point of failure and downtime?

Existing legacy applications will already have groupings of applications per application server or machine based upon operational experience and the above criteria. In a pure “lift and shift” scenario for example the entire application server can be put in one container.

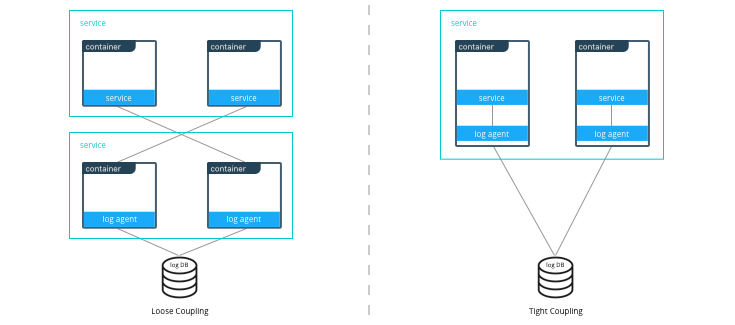

Similarly with microservices, the same criteria apply. For example, consider a microservice that depends on a logging agent to push logs to a centralized logging database. The following diagram shows two different strategies for a high availability deployment for the microservice.

If the microservice and logging agent are loosely coupled, they can be run in separate containers such as in the configuration on the left. However, if the service and the logging agent are tightly coupled and their release lifecycles are identical, then putting the two processes in the same container can simplify deployments and upgrades as illustrated in the configuration on the right. To manage multiple processes there are several lightweight init systems for containers such as tini, dumb-init, and runit.

Hardening Images¶

A question that arises frequently is which parts of the component should go into an image? The engine or server, the application itself, the configuration files? There are several main approaches:

- Create only a base image and inject the things that vary per release or environment

- Create an image per release and inject the things that vary per environment

- Create an image per release and environment

In some cases, a component does not have an application associated with it or its configuration does not vary per environment, so a base image is appropriate. An example of this might be a reverse proxy or a database. In other cases such as an application which requires an application server, using a base image would require mounting a volume for a certain version of an application.

The following table summarizes the advantages and disadvantages of each choice:

| Base Image | Release Image | Environment Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| What’s inside the image | OS, middleware, dependencies | Base image, release artifacts, configuration generic to the environment | Release image, configuration specific to the environment |

| What’s outside the image | Release artifacts, configuration, secrets | Configuration specific to the environment, secrets | Secrets |

| Advantages | Most flexible at run time, simple, one image for all use cases | Some flexibility at run time while securing a specific version of an application | Most portable, traceable, and secure as all dependencies are in the image |

| Disadvantages | Less portable, traceable, and secure as dependencies are not included in the image | Less flexible, requires management of release images | Least flexible, requires management of many images |

| Examples | Tomcat

dtr.example.com/base/tomcat7:3 |

Tomcat + myapp-1.1.war

dtr.example.com/myap p/tomcat7:3 |

Tomcat + myapp-1.1.war + META-INF/context.xml

dtr.example.com/myapp/tomcat7:3-dev |

Usually a good choice is to use a release image. This gives the best combination of a sufficiently immutable image while maintaining the flexibility of deploying to different environments and topologies. How to configure the images per different environments is discussed in the next section.

Configuration Management¶

A single enterprise application will typically have four to twelve

environments to deploy on before going into production. Without Docker

installing, configuring, and managing these environments, a

configuration management system such as Puppet, Chef, Salt, Ansible,

etc. would be used. Docker natively provides mechanisms through

Dockerfiles and docker-compose files to manage the configuration of

these environments as code, and thus configuration management can be

handled through existing version control tools already used by

development teams.

Environment Topologies¶

The topologies of application environments can be different in order to optimize resources. In some environments it doesn’t make sense to deploy and scale all of the components in an application stack. For example, in functional testing only one instance of a web server is usually needed whereas in performance testing several instances are needed, and the configuration is tuned differently. Some common topologies are:

- Development — A single instance per component, debug mode

- Integration, Functional testing, UAT, Demonstration - A single instance per component, small dataset, and integration to test external services, debug mode

- Performance Testing — Multiple instances per component, large dataset, performance tuning

- Robustness Testing — Multiple instances per component, large dataset, integration to test external services, batch processing, and disaster recovery, debug mode

- Production and Staging — Multiple instances per component, production dataset, integration to production external services, batch processing, and disaster recovery, performance tuning

The configuration of components and how they are linked to each other is

specified in the docker-compose file. Depending on the environment

topology, a different docker-compose can be used. The

extends

feature can be used to create a hierarchy of configurations. For

example:

myapp/

common.yml <- common configurations

docker-compose-dev.yml <- dev specific configs extend common.yml

docker-compose-int.yml

docker-compose-prod.yml

Configuration Buckets¶

In a typical application stack there are tens or even hundreds of

properties to configure in a variety of places. When building images and

running containers or services there are many choices as to where and

when a property should be set depending on how that property is used. It

could be in a Dockerfile, docker-compose file, environment variable,

environment file, property file, entry point script, etc. This can

quickly become very confusing in a complicated image hierarchy

especially when trying to adopt DRY principles. The following table

shows some common groupings based on lifecycles to help determine where

to put configurations.

| When | What | Where | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yearly build time | Enterprise policies and tools | Enterprise base image Dockerfiles | FROM centos6.6RUN yum -y --noplugins install bzip2 tar sudo curl net-tools |

| Monthly build time | Application policies and tools | Application base image Dockerfiles | COPY files/dynatrace-agent-6.1.0.7880-unix.jar /opt/dynatrace/ |

| Monthly/weekly build time | Application release | Release image Dockerfiles | COPY files/MY_APP_1.3.1-M24_1.war /opt/jboss/standalone/deployments/ |

| Weekly/daily deploy time | Static environment configuration | Environment variables, docker-compose, .env | environment:-MOCK=true-GATEWAY_URL=https://example.com/ws |

| Deploy time | Dynamic environment configuration | Secrets, entrypoint.sh, vault, CLI, volumes | $ curl -H "X-Vault-Token: f3b09679-3001-009d-2b80-9c306ab81aa6" -X GET https://vlt.example.com:8200/v1/secret/db |

| Run time | Elastic environment configuration | Service discovery, profiling, debugging, volumes | $ consul-template -consul consul.example.com:6124 -template "/tmp/nginx.ctmpl:/var/nginx/nginx.conf:service nginx restart" |

The process of figuring out where to configure properties is very similar to code refactoring. For example, properties and their values that are identical in child images can be abstracted into a parent image.

Secrets Management¶

Starting with Mirantis Container Runtime 17.03 (and Docker CS Engine 1.13), native secrets management is supported. Secrets can be created and managed using RBAC in Docker Enterprise. Although Docker EE can manage all secrets, there might already be an existing secrets management system, or there might be the requirement to have one central system to manage secrets in Docker and non-Docker environments. In these cases, a simple strategy to adopt for Docker environments is to create a master secret managed by Docker EE which can then be used in an entry point script to access the exiting secrets management system at startup time. The recovered secrets can then be used within the container.

Dockerfile Best Practices¶

As the enterprise IT landscape and the Docker platform evolve, best practices around the creation of Dockerfiles have emerged. Docker keeps a list of best practices on docs.docker.com.

Docker Files and Version Control¶

Docker truly allows the concept of “Infrastructure as Code” to be applied in practice. The files that Docker uses to build, ship, and run containers are text-based definition files and can be stored in version control. There are different text-based files related to Docker depending on what they are used for in the development pipeline.

- Files for creating images — Dockerfiles,

docker-compose.yml,entrypoint.sh, and configuration files - Files for deploying containers or services —

docker-compose.yml, configuration files, and run scripts

These files are used by different teams from development to operations in the development pipeline. Organizing them in version control is important to have an efficient development pipeline.

If you are using a “release image” strategy, it can be a good idea to separate the files for building images and those used for running them. The files for building images can usually be kept in the same version control repository as the source code of an application. This is because release images usually follow the same lifecycle as the source code.

For example:

myapp/

src/

test/

Dockerfile

docker-compose.yml <- build images only

conf/

app.properties

app.xml

entrypoint.sh

Note

A docker-compose file with only

build

configurations for different components in an application stack can

be a convenient way to build the whole application stack or

individual components in one file.

The files for running containers or services follow a different lifecycle, so they can be kept in a separate repository. In this example, all of the configurations for the different environments are kept in a single branch. This allows for very simple version control strategy, and configurations for all environments can be viewed in one place.

For example:

myapp/

common.yml

docker-compose-dev.yml

docker-compose-int.yml

docker-compose-prod.yml

conf/

dev.env

int.env

prod.env

However, this single branch strategy quickly becomes difficult to maintain when different environments need to deploy different versions of an application. A better strategy is to have each environment’s run configuration is in a separate branch. For example:

myapp/ <- int branch

docker-compose.yml

conf/

app.env

The advantages of this are multiple:

- Tags per release can be placed on a branch, allowing an environment to be easily rolled back to any prior tag.

- Listing the history of changes to the configuration of a single environment becomes trivial.

- When a new application release requires the same modification to all of the different environments and configuration files, it can be done using the merge function from the version control as opposed to copying and pasting the changes into each configuration file.

Repositories for Large Files¶

When building Docker images, inevitably there will be large binary files that need to be used. Docker build does not let you access files outside of the context path, and it is not a good idea to store these directly in a version control, especially a distributed one such as git, as the repositories will rapidly become too large and unwieldy.

There are several strategies for storing large files:

- Web Server — They can be stored on a shared filesystem, served by

a web server, and then accessed by exposing them with the

ADD <URL> <dest>command in the Dockerfile. This is the easiest method to setup, but there is no support for versions of files or RBAC on files. - Repository Manager — They can be stored as files in a repository manager such as Nexus or Artifactory, which provide support for versions and RBAC.

- Centralized Version Control — They can be stored as files in a centralized version control system such as SVN, which eliminates the problem of pulling all versions of large binary files.

- Git Large File Storage — They can be stored using Git LFS. This gives you all of the benefits of git, and the Docker build is under one context. However, there is a learning curve to using Git LFS.

Summary¶

This document discusses best practices for modernizing traditional applications to Docker. It starts with high-level decisions such as what applications to Dockerize and methodology, then moves on to more detailed decisions such as what components to put in images, what configuration to put in containers, where to put different types of configuration, and finally how to store assets for building images and configuration in version control. Follow these best practices to modernize your traditional applications.